We now need to make weather forecasts available to everyone since they are far more accurate.

- byAdmin

- May 10, 2024

- 1 year ago

Thirty years later, a four-day prediction is just as accurate as one made one day ago.

Many people think of weather predictions as merely being good to have. Practical for arranging a Sunday cookout or determining whether an umbrella is required for the day. However, weather forecasts are vital in many aspects—they may literally mean the difference between life and death.

By providing early warnings of storms, heat waves, and calamities, accurate predictions can save lives. They are used by farmers for agricultural management, which can mean the difference between a bountiful or unsuccessful crop. For the purpose of determining how much electricity they will receive from wind and solar farms, grid operators rely on precise temperature forecasts for both heating and cooling needs. For the safe transport of passengers across seas, pilots and sailors depend on them. Accurate forecasting of the weather is frequently crucial.

Weather forecasting have significantly improved.

Forecasting weather has advanced significantly. The Babylonians attempted to forecast weather patterns about 650 B.C. by observing the motions and patterns of the clouds. In his work Meteorologica, written three centuries later, Aristotle described the formation of several phenomena, including lightning, rain, hail, and hurricanes. Although a lot of it proved to be incorrect, it is one of the earliest attempts to provide a detailed explanation of how the weather operates.

The first weather prediction for ships was not released by the UK's Meteorological Service (the Met Office) until 1859. It made its first public weather forecast two years later. Although meteorological data have improved throughout time, the use of computerised numerical modelling has resulted in a huge step-change in forecasts. It was not until the 1960s, a century later, that this began.

It was then, and forecasts have much improved. Different national meteorological organisations and a variety of measures show this.

As compared to thirty years ago, the Met Office claims that its four-day predictions are now just as accurate as its one-day ones.

In the US as well, predictions have improved significantly. Some of the most significant forecasts, such as those for hurricanes, demonstrate this.

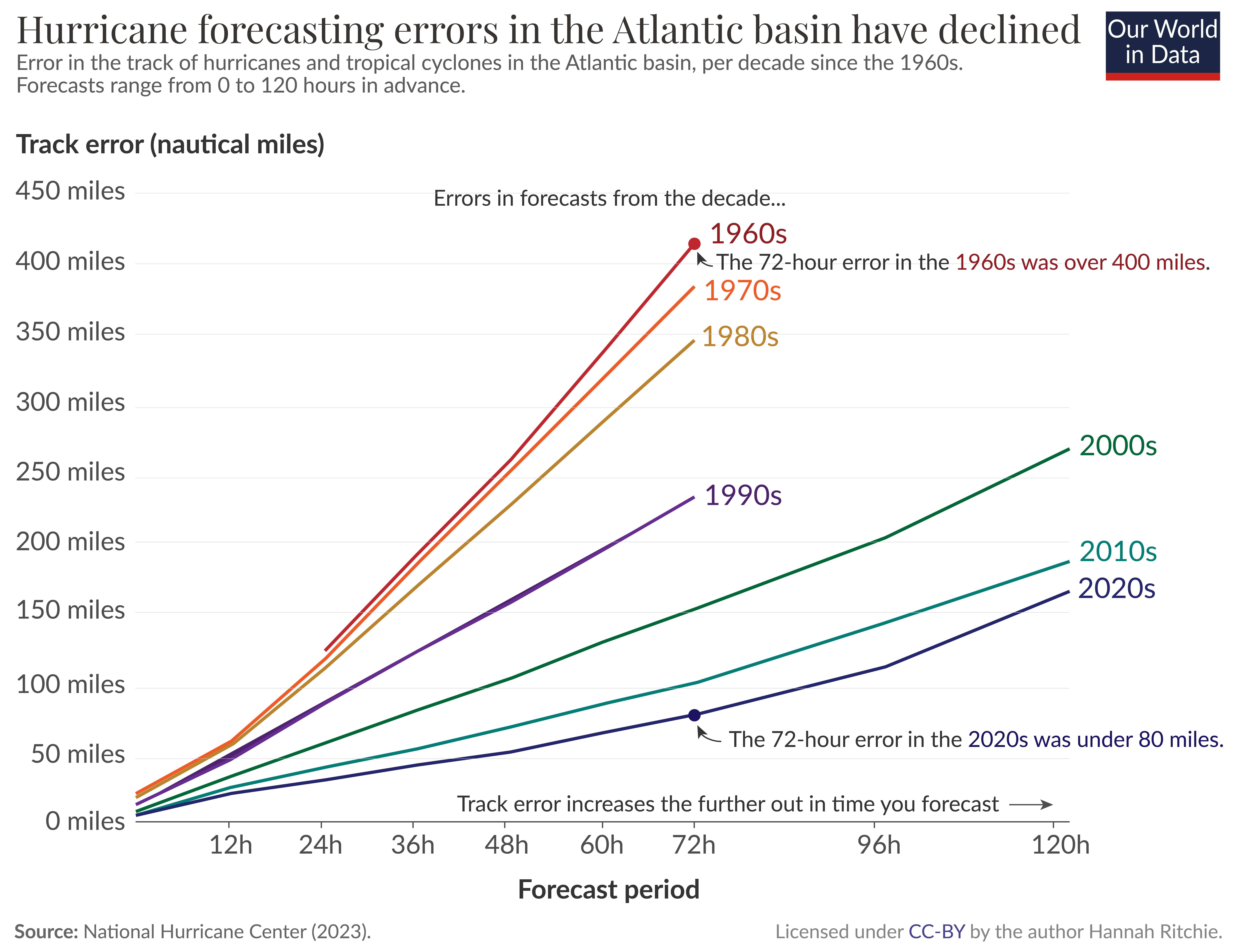

Information on the "track error"—the deviation in the hurricane's path—of cyclones and hurricanes is released by the National Hurricane Centre. In the chart below, this is displayed starting in the 1960s..

The forecast error for various time periods ahead of time is represented by each line. For instance, it may occur 12 hours, 120 hours, or 5 days in advance.

This track error has clearly reduced with time, particularly for longer-term projections. A 48-hour forecast's inaccuracy in the 1970s was between 200 and 400 nautical miles; nowadays, it is about 50 nautical miles.

We have another way to display the same facts. Each line in the chart below reflects the average error for a given decade. We have the predicted period on the horizontal axis, which again spans from 0 to 120 hours.

In the 1960s and 1970s, there was a 72-hour inaccuracy of more than 400 nautical miles. It's less than 80 miles now.

Today, meteorologists can forecast a hurricane's location with reasonable accuracy up to three or four days ahead of time, allowing villages and cities to make preparations and avoiding needless evacuations that may have occurred in the past.

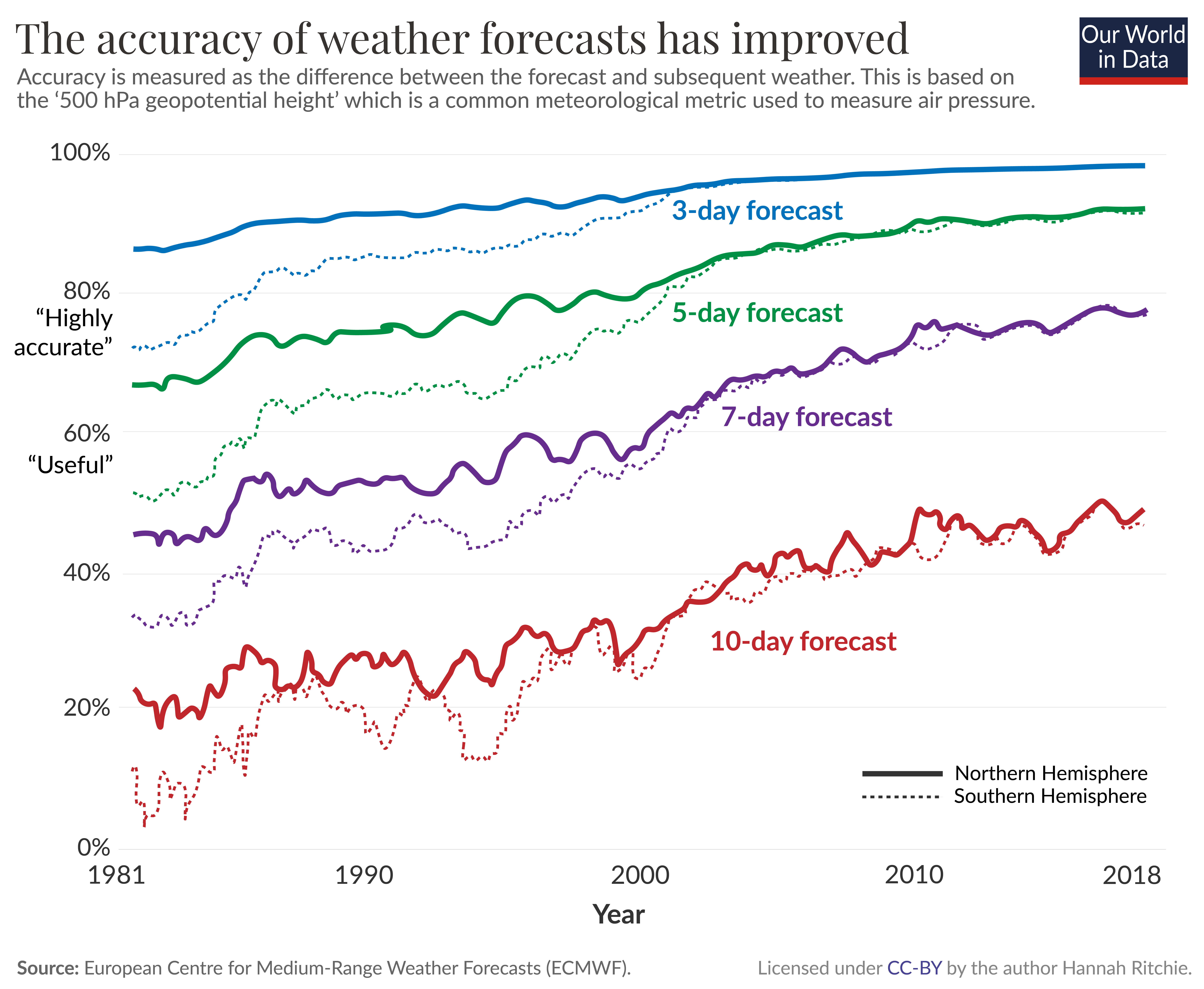

Global numerical weather models are created by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). Although local forecasts are obtained by national weather agencies through considerably higher-resolution processing, these global models are an essential input to these systems.

Over time, the ECMWF releases studies of its mistakes. This is represented in the chart below.1. For forecasts made three, five, seven, and ten days in advance, it displays the discrepancy between the expected and actual weather conditions. This measurement is called the "500 hPa geopotential height," which is a widely used air pressure metre in meteorology (which determines weather patterns).

The Northern Hemisphere is represented by the solid line, and the Southern Hemisphere by the dashed line.

Since the 1980s, three-day predictions (highlighted in blue) have been reasonably accurate and have continued to improve with time. The accuracy now stands at about 97%.

The longest durations have seen the most benefits. Five-day predictions were "very accurate" by the early 2000s, and seven-day forecasts are already approaching that level of accuracy. While not quite there yet, 10-day projections are improving.

The weather is then predicted using these data as input into numerical prediction models. This leads to the following two developments. These versions are now operated on considerably quicker processors. Increased speed is essential since the Met Office now divides the world into grids with ever fewer squares. They have now reduced the size of their global model to a grid of 1.5 km squares, from 90 km wide squares. Thus, a great deal more computations are required to obtain this high-resolution map. Additionally, techniques for converting data into model outputs have been refined. We've progressed from really simplistic worldviews to techniques that can precisely represent the intricacy of these systems.

The way these projections are shared is the last important consideration. Daily updates were exclusively available in the daily newspaper not so long ago. You can receive a few notices each day due to the growth of radio and television. We can now access real-time updates on our cellphones or over the internet.

Forecasts in low-income nations are even poorer, and they frequently lack early warning systems.

I can quickly pull up an app on my phone at home in Scotland and receive a quite accurate five-day prediction. Regretfully, not everyone has access to information of this calibre. Globally, weather forecasts vary greatly, and wealth disparities are also widespread.

In many affluent nations, a one-day prediction may not be as accurate as a seven-day prognosis, as documented in a recent work by scholars Manuel Linsenmeier and Jeffrey Shrader.3.

The quality disparity is nearly as large now as it was in the 1980s, despite the fact that national predictions have been better over time at all income levels.

This is due to a few factors. First, in impoverished nations, much fewer radiosondes and land-based devices measure meteorological data. Secondly, there are many fewer reports made.

Considering how much money is spent on weather and climate data, this is not unexpected. Lucian Georgeson, Mark Maslin, and Martyn Poessinouw examined how spending varied throughout income levels in a report that was published in Science.4 Spending by the public and private sectors on goods that are classified as "weather and climate information services" is included in this.

In the graphic below, this is shown as spending per person and as spending as a percentage of GDP.

Compared to high-income nations, low-income countries spend 15–20 times less per person. Nevertheless, they really spend more as a percentage of GDP considering the size of their economies.

Why are weather forecasts more accurate now?

These gains are explained by a few significant advancements.2.

The data has improved, which is the first significant change. The weather models may be updated with observations that are more comprehensive and have greater resolution. This is a result of both the increased coverage and improved quality of our satellite data as well as the increased density and coverage of land-based stations around the world. These instruments' accuracy has also increased.

Considering how much money is spent on weather and climate data, this is not unexpected. Lucian Georgeson, Mark Maslin, and Martyn Poessinouw examined how spending varied throughout income levels in a report that was published in Science.4 Spending by the public and private sectors on goods that are classified as "weather and climate information services" is included in this.

In the graphic below, this is shown as spending per person and as spending as a percentage of GDP.

This gap presents an issue. Arguably the most weather-dependent industry, agriculture employs 60% of labourers in low-income nations. Most are small-scale farmers, many of whom live in abject poverty.

Farmers can make better judgements if they have access to reliable weather forecasts. They can learn when it's ideal to sow their crops. They are aware of when irrigation will be most important and when fertilisers may be in danger of washing away. In order to either preserve pesticides while the risk is minimal or defend their crops when an assault is imminent, growers can receive notifications regarding pest and disease outbreaks. This implies that if they have access to precise weather forecasts, they can make the most use of their limited resources.

For the world's poorest inhabitants, accurate weather forecasts are especially important.

They are also essential for providing defence against storm surges, floods, heat waves, and cyclones. Accurate projections that arrive a few days ahead of schedule enable towns and cities to get ready. It is possible to safeguard housing and have emergency services available to aid in the healing process.

However, precise projections by themselves are insufficient to address the issue; people must be informed in order for them to take appropriate action. Over the past few decades, many of the biggest tragedies have been precisely predicted in advance. A typical shortcoming was inadequate communication.

Forecast improvement is the cornerstone. However, these must also be included in early warning systems that work. According to estimates from the World Meteorological Organisation, almost one-third of the world's population—mostly those in the poorest nations—does not have them.

It is undervalued to improve projections, particularly in low-income nations.

In many areas of the world, we take accurate weather predicting and distribution for granted after significant advancements in recent decades. It would be different if everyone had access to this.

This will become increasingly more crucial when the likelihood of weather-related disasters rises due to climate change. The poorest people will ultimately bear the brunt of the effects since they are the most vulnerable. Effective adaptation to climate change requires improved forecasting.

To address the gaps, appropriate financial support and investment will be necessary.

Additionally, new technologies have the potential to speed things up. A novel artificial intelligence (AI) system called Pangu-Weather, which can provide forecasts as precisely (or better) than top meteorological organisations up to 10,000 times faster, was recently described in a report published in Nature.Six 39 years of historical data served as its training set. Because of their speed, these projections might yield significantly better outcomes for nations with tight resources and be much less expensive to run.

To address the gaps, appropriate financial support and investment will be necessary.

Additionally, new technologies have the potential to speed things up. A novel artificial intelligence (AI) system called Pangu-Weather, which can provide forecasts as precisely (or better) than top meteorological organisations up to 10,000 times faster, was recently described in a report published in Nature.Six 39 years of historical data served as its training set. Because of their speed, these projections might yield significantly better outcomes for nations with tight resources and be much less expensive to run.

When there are gaps in the availability of land-based weather stations, faster and more effective technologies can also fill them. Drones equipped with sensors may conduct surveys over particular regions to create maps with greater detail. Mobile technologies can swiftly disseminate this information since they provide more cost-effective and efficient methods of converting that into projections. Farmers in low-income nations are already receiving texts from some corporations advising them on when to sow their crops.

This invention is essential to building nations that can withstand today's weather. However, in a world where more extreme weather is predicted, it is also important.

Post a comment

Hot Categories

Recent News

Video: Shah Rukh Khan shares daughter Suhana's debut film The Archies teaser

- May 1, 2024

- 1 year ago

Top Travel Deals & Packages You Can’t Miss – Best Discounts of the Year

- Aug 26, 2025

- 3 months ago

Daily Newsletter

Get all the top stories from Blogs to keep track.

0 comments